On Saturday, November 20, a diverse sample of the Greenville County community gathered outside Mt. Sinai Baptist Church to remember the lynching of Tom Keith. On August 16, 1899, Mr. Keith, an elderly African American man, was lynched by a white mob. More than 122 years later, a marker memorializing Mr. Keith’s story has now been installed and unveiled, thanks in large part to the careful historical work of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) and the grassroots efforts of the Community Remembrance Project (CRP) of Greenville County.

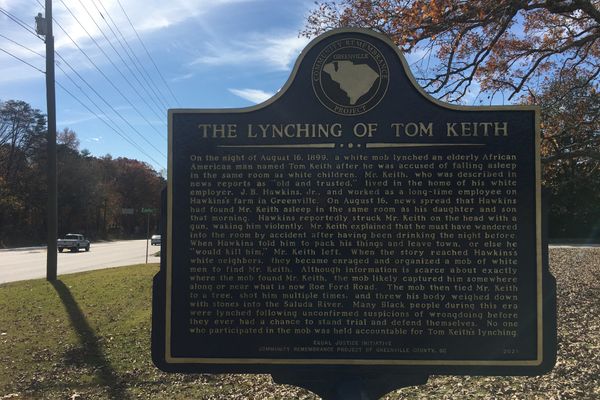

The maker is located on Furman-owned property less than a mile from campus, in a field just east of Mt. Sinai Baptist Church, at the intersection of Roe Ford Road and Highway 25. The main side of the marker reads as follows:

On the night of August 16, 1899, a white mob lynched an elderly African American man named Tom Keith after he was accused of falling asleep in the same room as white children. Mr. Keith, who was described in news reports as “old and trusted,” lived in the home of his white employer, J.B. Hawkins, Jr., and worked as a long-time employee on Hawkins’s farm in Greenville. On August 16, news spread that Hawkins had found Mr. Keith asleep in the same room as his daughter and son that morning. Hawkins reportedly struck Mr. Keith on the head with a gun, waking him violently. Mr. Keith explained that he must have wandered into the room by accident after having been drinking the night before. When Hawkins told him to pack his things and leave town, or else he “would kill him,” Mr. Keith left. When the story reached Hawkins’s white neighbors, they became enraged and organized a mob of white men to find Mr. Keith. Although information is scarce about exactly where the mob found Mr. Keith, the mob likely captured him somewhere along or near what is now Roe Ford Road. The mob then tied Mr. Keith to a tree, shot him multiple times, and threw his body weighed down with stones into the Saluda River. Many Black people during this era were lynched following unconfirmed suspicions of wrongdoing before they ever had a chance to stand trial and defend themselves. No one who participated in the mob was held accountable for Tom Keith’s lynching.

Prior to the unveiling of the marker, a brief program was held under an open-air tent on site. Feliccia Smith, a North Greenville University professor and co-chair of the Community Remembrance Project of Greenville County, gave opening remarks placing the lynching of Mr. Keith in broader historical context. Lynching in America was “the most public and notorious form of racial terrorism” in the service of an ideology of white supremacy, according to the reverse side of the marker.

Jalen Elrod, a local activist who is third vice chair of the South Carolina Democratic Party, read Mr. Keith’s story to attendees, and Toney Parks, senior pastor of Mt. Sinai Baptist Church, offered a prayer. Longtime City Councilwoman and Furman alumnae Lillian Brock-Flemming spoke in state Representative Chandra Dillard’s absence, emphasizing the importance of remembering and re-telling the truth about our history and asking those present to commit to “say what is right and do what is right.”

“And what is right?” Flemming asked the audience. A few voices shouted back the response she had been waiting for, from Micah 6:8: “to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God.”

The crowd was also graced by a pair of musical performances from Loretta Holloway, South Carolina’s Official First Lady of Song, including a reinterpretation of “Strange Fruit,” the extended metaphor on lynching first made famous by Billie Holiday over 80 years ago.

Another guest, Gabrielle Daniels, shared a few words in her capacity as a project manager for EJI. Based on Montgomery, AL, the Equal Justice Initiative was founded as a legal nonprofit in 1989 by criminal justice attorney Bryan Stevenson. (A well-known client of Mr. Stevenson, Anthony Ray Hinton, spoke at Furman in 2019 about his experience spending thirty years on death row for a crime he did not commit.) In addition to its work in the criminal justice system, EJI founded the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum, which chronicle the history of racism in America. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice includes two memorial monuments for every county in which documented lynchings took place. Community Remembrance Projects like the one that sponsored Saturday’s event “[empower] communities to change the physical landscape to honestly reflect our history.” A Greenville News article earlier this year summarized the relationship between the Community Remembrance Project and EJI’s national effort:

The role of the Remembrance Project is to research the [four] lynchings in Greenville County, to educate the public, to collect soil from the site of each killing, and to erect a historical marker to memorialize each victim. One jar of soil is sent to the Equal Justice Initiative. The other stays in Greenville. ... Ultimately, the [four] lynchings will be researched, soil will be collected and displayed publicly, and a marker will be created for each man. When the project is complete, the Community Remembrance Project will retrieve a duplicate of the Greenville County monument on display at the National Memorial.

The unveiling of the marker was followed by a moment of silence, after which the community joined in singing the second verse of the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” commonly referred to as the Black National Anthem:

Stony the road we trod,

Bitter the chastening rod,

Felt in the days when hope unborn had died;

Yet with a steady beat,

Have not our weary feet

Come to the place for which our fathers sighed?

We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,

We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered,

Out from the gloomy past,

'Til now we stand at last

Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.