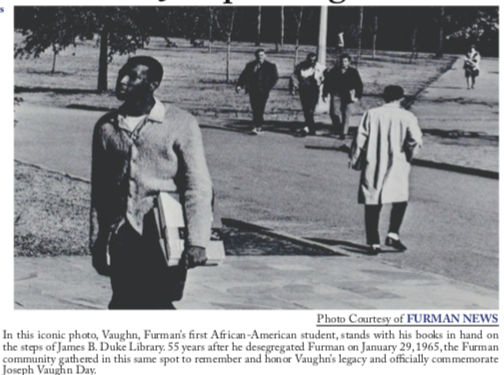

On Wednesday, January 29, the 55th anniversary of Furman’s desegregation, the university recognized the bravery of its first African-American student, Joseph Vaughn ‘68. At 12:15, hundreds of students, faculty, and administration officials gathered on the steps of James B. Duke Library—the spot of an iconic photo of Vaughn’s groundbreaking time at Furman. They processed to Daniel Chapel, alongside Vaughn’s friends and family, to remember Furman’s desegregation and celebrate the official commemoration of Joseph Vaughn Day.

The event featured speeches from President Davis, Trustee Alec Taylor, Director of the Center for Inclusive Communities Deborah Allen, Vaughn’s cousin Marcus Tate, and Rodney Acker, who desegregated Furman Athletics in 1969. According to history professor Stephen O’Neill, who served on the Task Force on Slavery and Justice and also spoke at the event, Furman’s effort to seriously grapple with its late arrival to desegregation—which occurred after the Civil Rights Act of 1964—manifested itself in 2015 with a publication entitled, “50 Years: Commemorating Desegregation At Furman, 1965-2015.”

The booklet, which recounts the circumstances of Furman’s desegregation, explains that Vaughn was handpicked for his “leadership and academic success and a personality that could handle the pressures of desegregation.” Upon enrolling at Furman in January of 1965—after the trustees voted to delay his initial admission—Vaughn emphasized that he had “the same dreams and aspirations” as his white classmates, and as one of those classmates would later recount, Vaughn “was not concerned about desegregating Furman. He was concerned about attending Furman.” Attend he did; during his time at the university, Vaughn “majored in English and minored in French,” joined several student organizations, acted in school plays and “served as chairman of the ‘Talk-a-Topic’ committee,” leading discussions on “race relations, the Vietnam War, and the student rights movements,” according to Furman’s report.

Following in his footsteps, English major Adare Smith ‘20 first shined a light on Vaughn’s legacy in 2019 when she organized what she described as a “march from the English Department to the library steps in Joseph Vaughn’s honor,” thus planting the seed for this year’s commemoration ceremony. Reflecting on the event, Smith noted that in addition to Greenville proclaiming January 29 as Joseph Vaughn Day, she was especially “excited to see members of Joseph Vaughn’s family on campus,” saying, “I think having them present here during the event was so vital in recognizing his honor. Those were the people who knew him and walked with him during his journey.”

Reflecting on the importance of remembering Vaughn, Smith explained that, “he took that first step and without him, who knows what Furman’s campus would look like today. He is a reminder that there are space and visibility for all students on campus.” Moreover, Smith emphasized that“creating spaces for students is something that must always be actively worked towards because those spaces aren’t inherent; they don’t come automatically.”

When asking celebration attendees about their thoughts and reflections on this historic ceremony, Dr. Brad Harmon, Assistant Dean for the First-Year and Second-Year Experience, echoed Smith’s comments, emphasizing that the work to make Furman a more inclusive campus requires “all members of the campus community working together” and has only just begun. Moving forward, Harmon added, “we first have to recruit individuals from marginalized and underrepresented backgrounds because until you have a diversity of thought and perspective, you truly cannot learn where you need to make a change.” Harmon also underlined the importance of giving marginalized communities the “necessary resources,”—or as Smith might say, “the space,”—to thrive.

To conclude the commemoration ceremony, Professor O’Neill directly addressed students in the audience, saying that “real change will only happen in the classrooms, on the ball fields, in your fraternities and sororities, in your student organizations, and in your dormitories.” He reminded attendees that we have come a long way since Joseph Vaughn took his first steps on campus 55 years ago, but we all still have much to do on an individual level to continue making Furman a more inclusive institution.

In this pursuit, perhaps we could each take a lesson from Francis Bonner, a Furman administrator who was serving as the University’s acting president when the trustees were making their final decision about Vaughn’s admission. According to the University website and records, just before the vote was taken, Bonner made “an impassioned plea for desegregation,” saying “you should do this not because the students and faculty urge it—which they do—not because it will be of financial benefit to Furman—which it will—and not because it is the Christian thing to do—which it definitely is. You should do this simply because it is the right thing to do!” That day, they officially admitted Vaughn and desegregated Furman. After 55 years, that still seems worthy of remembrance and celebration.