Forty years ago, on Sept. 5, 1977, the space probe Voyager 1 left Cape Canaveral, Florida en route to the outer solar system. This probe was the culmination of decades of planetary research, designed to explore the never-before-seen outer planets.

When, two years later, Voyager reached its first stop, the gas giant Jupiter, hundreds of NASA scientists worked around the clock to make sure everything ran smoothly. Armed with cameras and instrumentation, Voyager’s arrival allowed scientists to study everything they could find in the short time it would be near the planet. For the first time in history, the swirling, red storm known as the Great Red Spot was seen up close and personal, and a ring system was discovered around Jupiter.

For co-investigator Alan Cummings, the big discovery was the stunning variety of moons around Jupiter. “All that orange and black on Io changed our thinking about the moons in the solar system. I think most of us thought they would all look more or less like our own Moon. But, wow, how wrong was that!” said Cummings.

For Dr. David Moffett, physics professor here at Furman, these images “rekindled my love of astronomy and of science in high school.” Voyager had discovered volcanoes outside Earth on Io, and showed that water might exist below Europa’s icy surface.

The next year, Voyager reached the ringed world of Saturn. Despite its calm appearance - Voyager discovered the presence of winds exceeding 1,000 mph. NASA scientists moved the intrepid space traveler into orbit around one of the moons of Saturn, Titan. Titan is the only moon in the solar system to have an extensive atmosphere. Although Voyager’s cameras could not penetrate the thick layers, it did detect hydrocarbons like methane, a key ingredient for life.

On its way out of the solar system, Carl Sagan convinced NASA to point Voyager’s camera back towards the inner solar system for one last look at this place that we all call home. In those pictures was one image that Carl Sagan called “The Pale Blue Dot.” He waxed poetically about what that image means and I highly suggest you look up his moving words.

Nowadays, Voyager 1 is nowhere near the Sun. In 2012, it became the first and only human-made object to make it out of the solar system and into interstellar space, over 13 billion miles away.

Ed Stone, Voyager Project Scientist, is still in awe of what Voyager has accomplished, “None of us knew, when we launched 40 years ago, that anything would still be working, and continuing on this pioneering journey. The most exciting thing they find in the next five years is likely to be something that we didn’t know was out there to be discovered.” NASA is planning on shutting down all instruments by 2030, but Voyager will continue speeding on in its orbit around the galaxy.

The Voyager mission left a large legacy behind. Three satellites to Jupiter and Saturn all had their beginnings in Voyager science. Jupiter had the Galileo and Juno missions, while Saturn had the Cassini-Huygens mission.

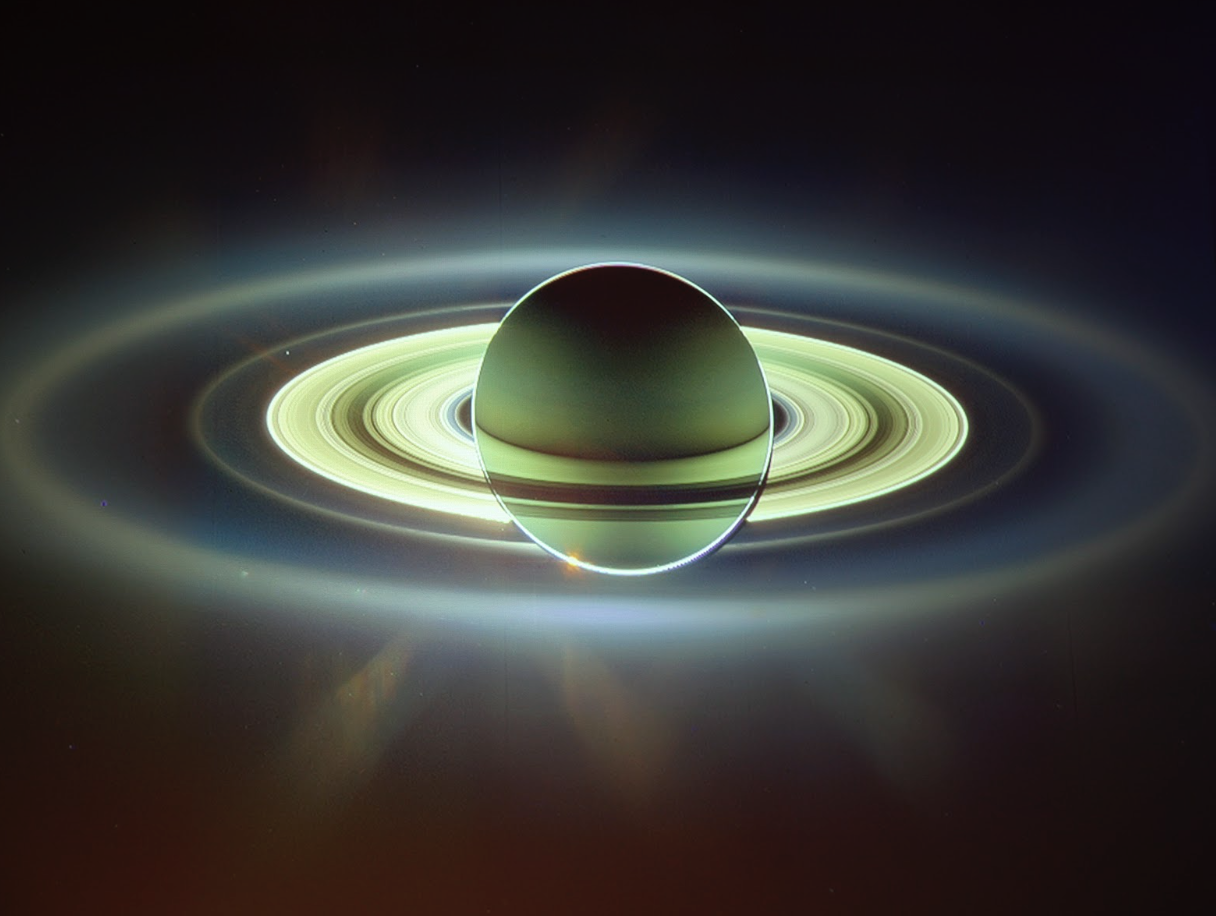

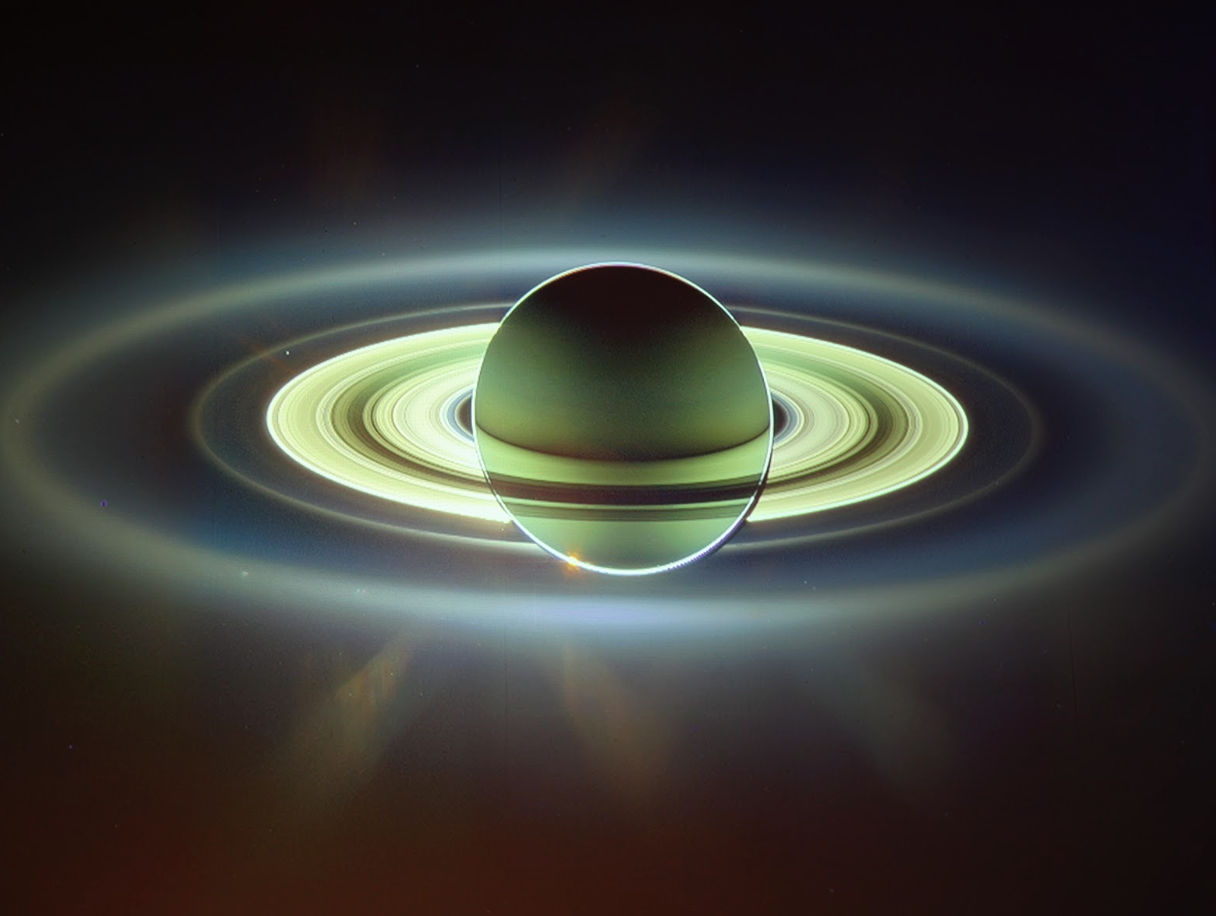

On Sept. 15, that Saturnian legacy will end. Cassini has been in orbit around Saturn since 2004, and has only enriched the knowledge we gained from Voyager. Whereas Voyager only glimpsed at the icy moon Enceladus, Cassini showed that it is still geologically active with ice geysers (called cryovolcanoes) erupting all the time. Cassini has also pierced the veil on Titan, landing the Huygens probe on the surface. There it found a hazy sky, the color of twilight. We know now that this smoggy world has methane lakes and flooded canyons.

With fuel in short supply, Cassini’s mission is nearing its end. However, NASA is determined to send it out with a bang. Right now, it is on its grand finale, flying between the inner rings and Saturn’s atmosphere every week. Its cameras are taking detailed pictures of Saturn’s atmosphere in attempt to figure out what makes Saturn tick. Since Enceladus and Titan could possibly have ingredients for life on them, at 6:31 AM EDT, NASA will command Cassini to dive into Saturn’s atmosphere, collecting data until data can no longer be collected. It is a spectacular end to a spectacular mission.

Some humans like myself struggle to plan long term. I cannot even plan what I’m having for dinner tonight, much less what I’m going to be doing in a five years. Yet NASA seems to have a knack for it. Both of these spectacular missions have increased our knowledge about our own neighborhood and placement in the universe. I can only hope that NASA continues to do what it does best and plan for our future in space.

If you’d like to learn more about space, space exploration, and NASA, contact Ray Garner, President of the Astronomy Club, at ray.garner@furman.edu.