At the beginning of March, the South Carolina House of Representatives voted to affirm cuts to the budgets of two state universities for assigning books with LGBT themes. USC-Upstate’s budget was cut by $17,142 for assigning Out Loud: The Best of Rainbow Radio to incoming freshmen, and the College of Charleston’s budget was cut by $52,000 for assigning the graphic novel Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Although the reductions in each university’s allotted funding is still pending the state senate’s approval of the general budget, the proposed cuts are equal only to the cost of each school’s summer reading program. This legislative decision offers an opportunity for us to reflect on the ways we approach LGBT and the language we use and the reasons we offer in such discussions.

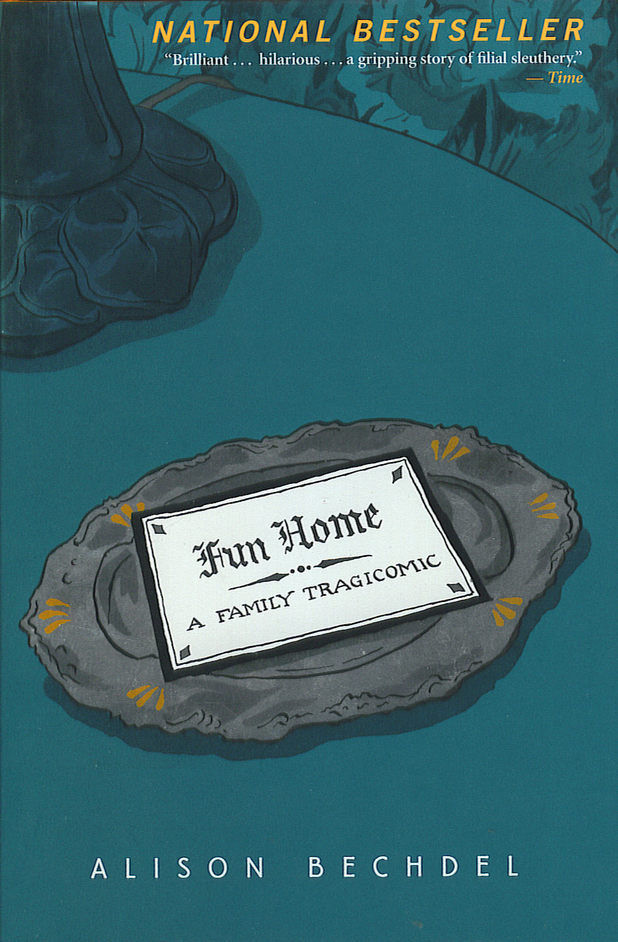

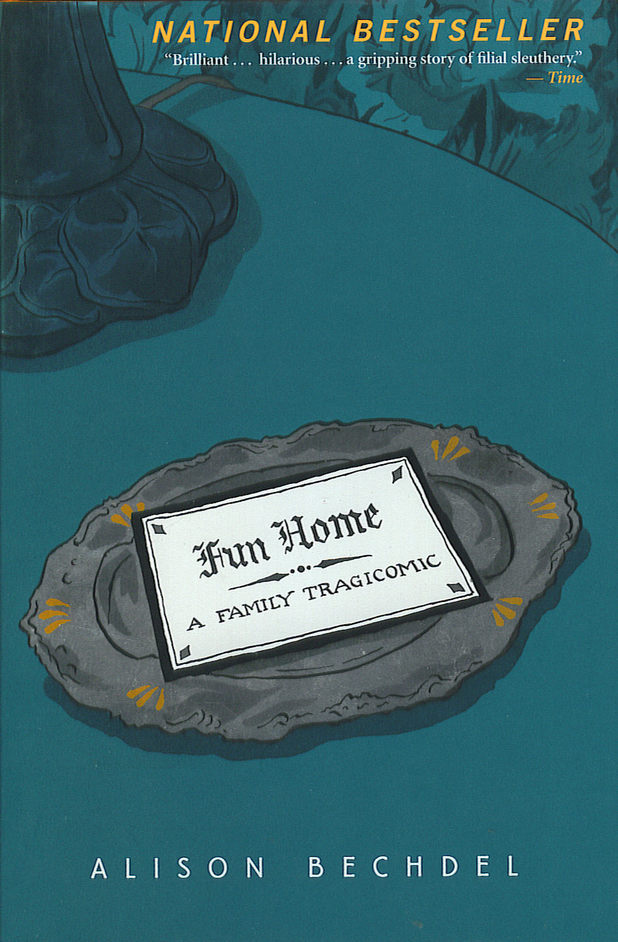

I have read Fun Home in two classes at Furman. Fun Home is a mature work about a mature subject. In it, the author remembers her father’s suicide, and explores their relationship through the lens of her own identity as a lesbian and her father’s relationships with other men. The work includes frank depictions of human sexuality and human bodies. These aspects of the text contribute to the fervor in the legislature surrounding Fun Home, with the graphic memoir branded as pornographic by many state officials, who describe the work as containing content that violates community standards of decency.

This case shows how we imbue the words we use to describe ideas and people with whom we disagree with a rhetorical power that covers over the realities of our argument. These kinds of arguments employ the language of disgust and appeal to a democratized sense of what is right and wrong but include no explicit consideration of what makes the object of concern right or wrong.

In this limited investigation, it does not matter whether or not Fun Home is pornographic, or whether or not it should be read in public universities. What matters in this consideration is how easily the language that often accompanies discussion of LGBT issues in South Carolina can be characterized by a self-justifying moral aversion. Discourses of disgust and alienation — rejection as a reflex — are inherently problematic.

I grew up in a small southern town in rural South Carolina, and I remember hearing in school almost every day derogatory sexual terms used as slurs by my fellow students to demean others. Children used the words carelessly, with little thought to what they meant, using insults to stigmatize and cause harm. In the mouth of a young student, those words were violent, used to cause pain and injury, expressions of power used to reinforce particular ways of life without regard for the lives of others.

The words and actions of my classmates were not wrong because their language caused pain — we say words that hurt other people all the time. Instead, in these cases disgust takes the place of reasons and rejection becomes a reflex, an instinctual reaction often explained by sentiment and appeals to precedent. Without the coarse language, many of the adults in my town spoke in the same terms, using bigger, more sophisticated words to talk about moral decency, history, and the threats that the gay and lesbian lifestyle pose to community norms. Without a framework of articulated reasons, the language that adults use to object to homosexuality are subdued versions of the shows of force , too similar to the slurs thrown about carelessly by young students who do not realize the significance of what they are saying.

Although I would disagree and aspire to challenge them, there are reasons — political, philosophical, religious, social, even scientific — for why a person might object to alternative sexual orientations. Legislators justifying the decision to cut money from the budgets of the College of Charleston and USC-Upstate have not offered these kinds of reasons. Instead, they have appealed to community standards of decency and labelled these works with words they have failed to define. This justification is inadequate — we cannot call homosexuality wrong just because we do not like it, we cannot minimize people just because we do not understand them, and we cannot refuse to read books simply because they offend us.